- Home

- Martha Long

Ma, I've Got Meself Locked Up in the Mad House

Ma, I've Got Meself Locked Up in the Mad House Read online

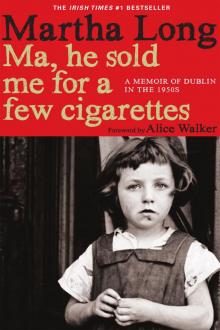

Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes

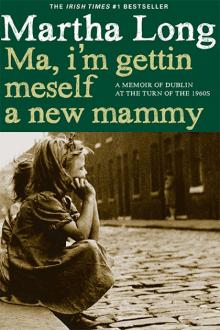

Ma, I’m Getting Meself a New Mammy

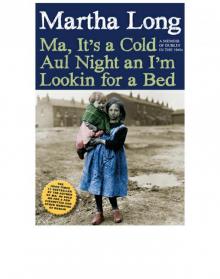

Ma, It’s a Cold Aul Night an I’m Lookin for a Bed

Ma, Now I’m Goin Up in the World

MA, I’VE GOT MESELF LOCKED UP IN THE MAD HOUSE

Martha Long

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licenced or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781780574059

Version 1.0

www.mainstreampublishing.com

Copyright © Martha Long, 2011

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

MAINSTREAM PUBLISHING COMPANY

(EDINBURGH) LTD

7 Albany Street

Edinburgh EH1 3UG

ISBN 9781845964481

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any other means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for insertion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author. In some cases, names of people and places, dates, sequences or the detail of events have been changed to protect the privacy of others. The author has stated to the publishers that, except in such respects, not affecting the substantial accuracy of the work, the contents of this book are true.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To the memory of my brother, who died tragically.

Oh! If only you were here now, there are so many things I would like to share with you, but all I can do now is remember you.

You were the quiet, shy one. The gentle one. You were content to stand in the shadows and let others take the limelight. But it was you who took centre stage, when devilment ended in trouble!

When you were little, they called you ‘The Lamp’, with your halo of gold-red hair. It couldn’t be missed, as it gloriously stood out among the crowd.

‘Yeah! It was him! “The Lamp” tha got us caught! Wit tha bleedin roarin head a hair of his!’

You would stand thinking about this, then your little face would light up, getting a fit of the giggles. It amused you, seeing them act so tragically.

Oh! But you were deep! When you were only little, I once asked you, ‘Why do you never say much?’

You said, ‘Cos I like hearin people talkin. How can ye listen if ye talk?’

You were seven years old, then our fate took us apart. You were a man of twenty-eight when we spoke again.

I see the exquisite tenderness in your eyes, as you proudly showed me your new baby daughter, cradled so lovingly in the palm of your open hands. I see the compassion in your eyes as you dip into your pockets to help out a poor unfortunate down on his luck. I see an ocean of pain and despair swimming in those velvet blue eyes as you look at me with unshed tears.

I tried to reach across the chasm, and pull you back from that despair, but it was too late. I was not there when you plunged out into the great unknown, heading away from this world, making for eternity.

Why? Why did the birds still sing and the world keep turning, when you, my little brother, had left us for ever?

You were only twenty-eight.

This world is a poorer place without you. I will not forget you. My last thoughts are of you, at night, when I whisper, ‘Sleep in peace, little brother, sleep in peace.’

To Bill, my friend; indeed he is! He is so very caring. But a word of caution, dear reader. I am only the author of this book, so don’t come looking to me for your money back. He is the publisher.

To Ailsa, my long-suffering editor. What a master! Only a genius such as her could make sense of someone who writes like me!

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Dear readers,

I suspect some of you may be confused why this book does not immediately pick up and continue the journey into the future. The answer is, quite honestly, I was now a young adult. Those years of my life became too personal and private. So, what I have done here is to pick up once again during a very dark time in my life. From then on, I must go back, searching the long and dark lonely roads of my past, trying to find where I lost my way.

Believe me, I am both privileged and warmed to know you may take that journey with me.

My very best wishes to you.

Martha Long

1

* * *

I rattled into the kitchen, feeling like a nomad in search of leafy bushes. My eyes peeled around, searching, then stopped, lighting on the kettle. Tea! My heart lurched with excitement. Have a cup of tea! I reached out to fill it.

No! Ye’re not getting any. No tea for you! Ye gave that up.

My heart dropped down into my thick woolly socks. I turned around, digging my hands deeper into the pockets of my red, romper-suit dressing gown. It was my day and evening wear, and, of course, I sleep in it. It was buttoned up to my neck. I bought it for a bargain in Dunnes Stores. Well, the sale sign said it was a bargain, so I bought it, believing them. Gobshite! I rambled down the road and discovered it sitting in another shop at half the price. Bleedin robbers! I’m not going back there again. Anyway, with my thermal granny nightdress underneath, I’m always ready for bed.

I gave a big sigh, snorting air out through my nose, and my chest complained, wheezing like bagpipes. Aah! I’m smoking too many cigarettes.

Good idea, have a smoke. Oh, yes! I felt myself lifting. Happiness is in a packet of roll-ups, I thought, reaching for the packet.

No! Forget it. Ye’re not having a smoke!

Jesus! What then? Something to eat? I asked meself timidly. Yeah! Toast and a boiled egg. Lovely. I cheered up immediately.

No! You gave that up, too. It was gradual, mind! Very gradual, like everything else you have done to yourself. But no! You have stopped eating. Another big sigh.

I wandered out to the hall and into the dining room, feeling like a displaced person. My body is trapped in the wrong mind. It’s dying for pleasure. But the mind is brutally perverse, utterly determined to stick with the mission of giving myself a slow and painful death. I stood in the middle of the grey, cold, lifeless room. Everything is spic and span. The fire is set, ready for lighting. I stared at it for a minute. No! I couldn’t be bothered lighting that. It would most definitely be too much trouble. I would only have to clean it out in the morning. So bloody freeze yourself.

I stood very still, listening to the emptiness of the room. There’s no life in it; no one lives here. The greyness of the evening, now turning even as I watch, is creeping into the darkness of the February night. A sudden gust of wind blew up, tearing and keening through the trees, shaking them in a fury. It looks like a storm is blowing up, I thought, staring out into the garden. I should do something . . . put on the light.

My eyes settled on the television in the corner. I could switch that on . . . but I made no move. Just continued to stare at the little grey box sitting in the corner. It’s been a long time since that came to life. When is this going to end? I felt as empty as the house; th

ere was nothing left I could punish myself with. I had deprived myself of all pleasure, even the basics for survival. This was indeed a slow death I was giving myself.

The doorbell rang. Jaysus! Who could that be? I leapt with excitement. I hadn’t spoken to anyone in a long time. They all got fed up with me, because I wouldn’t accept their invites to do anything or go anywhere. I even stopped inviting friends here for dinner. So the passage of time has dimmed their memory of me. Now I’m forgotten. I could call myself Martha Who? Hmm, I really am perverse.

I dashed to open the front door. It could be Jack the Ripper for all I care. I’m not choosy; I’d yank him off his feet and drag him in. Yeah! I’m desperate. When you’re as desperate as me, anything is better than talking to yourself.

I whipped the door open. Sister Eleanor!

‘Ah, hello, Martha. How are you, pet?’ she crooned, flying in the door and reaching out to give me a tight hug.

I held on for dear life. She’s just what the doctor ordered, I thought, grabbing her by the arm and rushing her into the sitting room. I was delirious with excitement, wanting anything to get rid of the painful, deep loneliness snaking its way around this barren house and coiling itself up through my body, leaving me with a terrible sense of desolation.

‘How are you, darling? Oh, I’ve been meaning to get up to see you. But we’ve been so busy in the convent,’ she said, giving me the mother-of-all-sorrows look. Then she leaned into me, readying herself to pump me with sympathy, empathy and any amount of understanding a body could want. I stared, slowly taking in a deep breath. She did the same, then held it, letting her nostrils flare.

‘Eh, not too bad,’ I rasped. That’s all I could get out! I’m still waiting for me voice box to heal after the operation a year ago to remove a rotten and diseased thyroid that was poisoning me.

‘Yes, it took us longer than we thought!’ the big beefy surgeon informed me. ‘It was twice the size of my hands,’ he said, holding out his fists in the air. I looked: they were like shovels. ‘It was wrapped around everything, completely diffused.

‘Your trachea was nearly cut off!’ he continued, reminding me of the day I nearly choked on me hamburger. ‘Yes,’ he said, shaking his head, a faraway look in his eyes, thinking about it. ‘Must have been growing for years. I never saw the like of it.’

‘So what have you been doing with yourself?’ Sister Eleanor breathed at me, making it sound like she was praying.

‘What?’ I blinked, trying to shake off the mist wafting over my eyes. ‘Oh, eh . . .’

I was dying to talk about myself – there’s nothing more fascinating – but nothing came out. I was blank. All my thoughts, all the anxieties, everything, just fell into a hole somewhere and a tight lid clamped shut over them. I was left feeling empty, confused. We stared at each other. I wanted to tell her . . . but tell her what?

‘Have you eaten? God, Martha! You are skin and bone! You’re not feeding yourself!’

I didn’t argue with that.

‘Look,’ she said, rushing over to the fireplace. ‘I’ll just put a match to this fire. It’s freezing in here!’ she said, shaking her shoulders, hoping I’d get the message.

‘No! Leave it, Sister Eleanor. I don’t want it lit!’

I felt suffocated by her fussing, and she was stampeding all over my newly cleaned room. I instantly felt very territorial; she was threatening the order I had imposed. It must remain exactly as I had it. Nothing can be touched, or I will fall into chaos! End up back where I started . . . I don’t know! Something dreadful will happen. I feel safe as long as I have order. Yeah, I know where I stand with order.

This is not order! the voice of sanity complained. This is nuts!

Fuck off! the winning perverse, broken-down side of me said.

I started to get agitated. ‘Sit down, Sister. Leave everything.’

‘But, Martha, you must have heat. Look, let me get you something to eat.’

‘No!’ I croaked, as loudly as I could wheeze out, sounding like a cat being strangled. ‘Leave me alone!’ I whined, filling up with despair and a sense of hopelessness.

‘What am I going to do? I can’t leave you like this!’

I stared into her face, afraid of the chaos she was creating and terrified of seeing her go out the door. She was the only person left in the world I wanted to talk to and trusted.

‘Martha,’ she started to say slowly, thinking. ‘Will you come down to the convent and stay overnight?’

‘The children’s part?’ I asked, ready to give a flat no.

‘Well, you would be staying in one of the children’s houses. It’s empty at the moment; they’re all away. But I’ll be there, and we could take you to see the doctor in the morning. Will you do that? You really need to see a doctor, pet.’

I hesitated, thinking about it. ‘I don’t know, Sister Eleanor. What can doctors do? They just fill you full of pills that don’t solve anything. The bloody pills just poison you, and they are very addictive. No, I don’t like pills, especially tranquillisers. I would be going around like a zombie! No, the only pills I’m taking are the ones I have to take daily, because I got rid of the thyroid, and I’m only taking those because they keep me alive. So that’s it. There’s no cure, Sister, for what’s wrong with me.’

‘What is wrong with you, Martha?’ she suddenly said, leaning down, staring at me, ready to hear my answer and produce the cure, probably from her big black leather handbag. I wonder what she carries around in that? I know she keeps a bottle of holy water, with the picture of Our Lady of Lourdes on it, and gives you a good sprinkle when she meets you. It’s her cure for everything.

‘Tell me, Martha!’ she said, giving me a poke in the arm.

I looked at her, not knowing what to say.

‘I want to know what’s wrong with you? Why are you hurting yourself?’

‘I wish I knew,’ I said, dropping my shoulders and looking around me, seeing only a prison.

We stared at each other, the air heavy with our wants. Her wanting me to see a doctor; me wanting her to wave a magic wand so the world will suddenly be lifted off my shoulders and we can jump up singing like Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music. ‘The hills are alive, with the sound of music’ – Sob, lovely!

The silence dragged on. I felt the hope vanishing down from my chest and out through my belly like greased lightning, leaving only a wisp of warmth. That too evaporated.

‘Look, Martha. You can’t stay here. Come on, we’ll go down to the convent. Things always look better in the morning.’ She grabbed my arm and propelled me out the door.

‘OK . . . but wait, I need to get dressed,’ I said, looking down at me romper-suit dressing gown.

‘No! You are fine as you are. Come on, let’s go.’

2

* * *

We drove in through the gates of the children’s house.

‘Right! Now, Martha. We’re here!’

I hesitated, not wanting to move. The security light beamed on, showing the convent across the fields. I shuddered, remembering the old days when I was locked up here.

But that was the old building. That’s now gone and replaced by a purpose-built, state-of-the-art modern convent, well away from the homes for the children.

What the hell am I doing here? Jesus! I left this place behind years ago. I’m getting out of here! I reached for the door handle, then stopped. She’s not going to give me a lift back. She’ll start bloody fussing, and I’m not in the mood to argue with her.

The hall door was open, then she was back.

‘Come along, Martha, quickly!’

I sat there, unsure what I wanted to do.

‘Are you all right?’ she asked, bending into the driver’s side. ‘Ah! Come along now,’ she said, rushing around to grab my arm and get me moving, steering me in the direction of the hall door. ‘You’ll be right as rain after a good night’s sleep,’ she clucked, banging the door shut behind her and locking it.

She rushed

past me, heading for the stairs. I stopped, looking at the children’s boots and bags and coats hanging in the hall. I was feeling uneasy, like I’d trapped myself. The clock was turning backwards. It should be going forward.

‘Ah, Martha! For God’s sake! Will you come on out of that and go to bed like a good girl.’

A what? Jesus Christ! Now she’s treating me like one of the children. I’m a grown woman in my thirties with a whole life behind me. But now I’ve put myself in her hands, and I feel more helpless than I did as a child.

I dragged myself up the stairs and followed her along the passage.

‘In here, Martha! This is the staff bedroom.’ She whipped down the bedcovers. ‘Now! In you get,’ she said, giving the pillows a hearty thump. ‘Now goodnight, God bless. Sleep well,’ and she was gone, out the door, leaving a draught behind her.

The room was still echoing, with dust flying and floorboards creaking as it tried to settle itself after a whirlwind had hit it.

Jaysus! I thought. That woman meets herself coming backwards, she moves so fast! I sniffed, staring at the door rocking on its hinges after she slammed it shut.

I sat up on the bed, propping the pillows against the headboard, and lay back, stretching out my legs. I suddenly felt the weariness and futility of hanging on like a pain of hot then cold air sweeping down from my chest and flying all around my body, then settling like a dead weight, paralysing me. Jesus! What happened to me? Why am I like this? Your woman is fussing around me like I’m a helpless child. And that’s what you’re letting her do! When did this start? How?

I closed my eyes, trying to think. Images flew across my brain.

I stopped. The doctor! That gobshite I went to see about the pain I’m always in. It has been crippling me for years. No one could explain it. But he could. ‘Left Limb Syndrome!’ he screeched to his audience of reluctant onlookers. Doctors he had dragged away from the other rooms in the clinic, trying to mind their own business and get on and see to the unfortunate patients waiting stoically for their turn.

Ma, I'm Gettin Meself a New Mammy

Ma, I'm Gettin Meself a New Mammy Ma, It's a Cold Aul Night an I'm Lookin for a Bed

Ma, It's a Cold Aul Night an I'm Lookin for a Bed Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes

Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes Ma, I've Got Meself Locked Up in the Mad House

Ma, I've Got Meself Locked Up in the Mad House Ma, Jackser's Dyin Alone

Ma, Jackser's Dyin Alone Ma, I've Reached for the Moon an I'm Hittin the Stars

Ma, I've Reached for the Moon an I'm Hittin the Stars Run, Lily, Run

Run, Lily, Run