- Home

- Martha Long

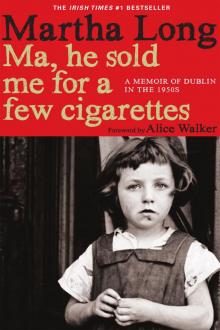

Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes

Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes Read online

To my most precious gifts, my children Fabian and MarieClaire

Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes

A Memoir of Dublin in the 1950s

Martha Long

SEVEN STORIES PRESS

NEW YORK

Copyright © 2007 by Martha Long

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by Mainstream Publishing Company, Edinburgh

First Seven Stories Press edition November 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the life, experiences and recollections of the author. In some cases, names of people, places, dates, sequences or the detail of events have been changed to protect the privacy of others. The author has stated to the publishers that, except in such respects, not affecting the substantial accuracy of the work, the contents of this book are true

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

www.sevenstories.com

College professors may order examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles for a free six-month trial period. To order, visit http://www.sevenstories.com/textbook" or send a fax on school letterhead to (212) 226-1411.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Long, Martha

Ma, he sold me for a few cigarettes : a memoir of Dublin in the 1950s / Martha Long. -- 1st Seven Stories Press ed.

p. cm.

“First published in Great Britain in 2007 by Mainstream Publishing Company, Edinburgh”--T.p. verso.

ISBN 978-1-60980-414-5 (hardcover)

1. Long, Martha--Childhood and youth. 2. Illegitimate children--Ireland--Dublin--Biography. 3. Abused children--Ireland--Dublin--Biography. 4. Poor children--Ireland--Dublin--Biography. 5. Dublin (Ireland)--Social conditions--20th century. 6. Dublin (Ireland)--Biography. I. Title.

DA995.D8L66 2012

941.835082’3092--dc23

[B]

2012029940

Typeset in Caslon and Sabon

Printed in the USA

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Foreword

Ma, He Sold Me For a Few Cigarettes, by Martha Long, is without question the most harrowing tale I have ever read. Even Charles Dickens, whom we appreciate for being the voice of so many abused children, is left in the dust. Why? Because Dickens was writing about abused children, while Martha Long was herself abused, horribly, unbelievably, by her mother’s “man” and by her own mother. Managing to stay alive, only just, by her own wits, in a world determined to erase her life and to make her believe, in her very soul, that she is nothing. It is a hair-raising read.

That it is a best seller in Ireland and England gives me hope. Martha Long is not being abandoned again. Still, it is so difficult a read one might ask: Why should we bother? We must bother because it begins to show us the deeper, perhaps most elemental source of our world’s despair: the chronic, horrific, sustained, abuse of children. Especially those children who, unwittingly, inherit the brutalities of colonialism, whether in Ireland, where this story is set, or the rest of the globe. I was amazed to feel some of the English, Irish, Scottish ancestors of both enslaved Africans and indentured Europeans (in the Americas) showing up in the characters of the Dubliners Martha Long depicts. There they are, in a Dublin slum in the 1950s, yes, (Martha Long’s childhood city), but recognizable as the same twisted beings who made life hell on earth for millions of people over the course of numerous centuries. And who, some of them, unfortunately, still walk among us.

As I read this book I thought: This is exactly why they’ve kept women ignorant for so long; why they haven’t wanted us to learn to read and write. “They” (you can fill this in) knew we would tell our stories from our point of view and that all the terrible things done to us against our will would be exposed, and that we would free ourselves from controlling pretensions, half-truths, and lies.

The destruction of our common humanity through the manipulation of imposed poverty, misogyny, alcoholism and drug abuse, is a major source of our misery, world-wide; and has been for a long time. Reading this startling testament to one child’s valiant attempts to live until the age of sixteen (four years to go!) is a worthy reminder that we can do better as adults if we turn to embrace the children who are suffering, anywhere on earth, who are coming toward us, their numbers increasing daily, for help.

—Alice Walker

April 2012

Acknowledgements

With thanks to my children Fabian and MarieClaire. Both of you a joy. Both, every mother’s dream, and I am the mother! Wonders will never cease. How lucky can I get?

To my firstborn Tina, always a special bond, and to her two little beauties, Charlie and William, my adorable grandchildren.

To Ailsa, my editor. Thank you for your extraordinary patience and most of all your warmth and your kindness.

To Bill, a very astute man. Thank you, Bill, I feel very privileged to have your faith in me.

A special thank you to Mary Dunne for tirelessly poring over my handwritten script and managing to type it all. Not an easy task. Take a bow, Mary!

Last but not least, to Helen Scully. Thanks, Helen, for all your encouragement. Without you this would not be in the public domain. Thanks, friend!

Author’s Note

This is the true story of my early childhood. Originally, I did not write it for publication. Instead, my intention was to rid myself of the voice of the little girl I had once been. For many years, I had tried to leave her behind and bury her in the deep, dark recesses of my mind. I tried to pretend she had never existed and went on to become someone she wouldn’t recognise. But she was always there in the background, haunting me and waiting for her chance to burst back into life and give voice to the pain she endured. I got old and tired before my time as I struggled to escape her, and, finally, the effort of suppressing her became too much. As I started to write, she exploded back into life, and I let her tell the story in her own voice.

1

The ma an me, an me mother’s sister, Nelly, an her son, Barney – he’s only three, I’m bigger, I’m nearly four – live together in one room in a tenement house in the Liberties of Dublin. We were all born here. Me aunts an uncles were born in this room, all ten of them, but most of them now live away in England, so it’s just Nelly an me ma left.

Me ma, Sally, had only just passed her sixteenth birthday when I arrived in the world. It was a shock te everyone, they said, though how her growin belly was not noticed was a mystery. The hawkeyed women missed tha one! When her brothers an sisters arrived over te find out wha was goin on, she wouldn’t tell anyone who the father was, an the local parish priest said me ma would have te go inta a Magdalen laundry te stop her getting inta more trouble. ‘The baby can go into a convent as well. The nuns are very good in these homes, they’ll take care of it.’ But Nelly said she would take care of us an told the rest of them te go back te England.

Me granny was a dealer in the Iveagh Market. She sold secondhand clothes, an on Sundays she’d have me grandfather take her apples, an oranges, an chocolate, an things on his horse an cart, an drive out te Booterstown at the seaside, where she sold them te the city people comin off the train te get the fresh air an let their childre play in the sand an get a good wash at the same time, runnin in an out of the water. Me granny worked very hard, gettin up at four o’clock in the mornin te be at the market in time te get her fruit an vegetables, or fish on Fridays.

Me

grandfather was a baker. He was a terrible man for the drink. An he was always angry. He didn’t make me granny’s life easy. He fought in the First World War, an he brought home a huge big paintin from a bombed church in Belgium. I don’t know how he managed te get away with tha an bring it all the way back te Dublin, but he did, an it used te hang in the back room (we don’t go inta tha room for some reason), takin up the whole wall. Now the paintin’s gone, cos Nelly sold it for drink.

Me poor granny lost four of her childre, one after another, an then me grandfather, within nine months. A three-year-old boy, he fell off a low wall an was killed. A little girl, she was only nine years old. A twelve-year-old girl, who died of pneumonia. She was late for school, an the doors were locked, so she sat on the cold steps of the school in the pourin rain, too frightened te go home. A neighbour saw her sittin there an told me granny. She ran down an found her still sittin there an soaked te the skin. Me granny took the shawl from aroun her head an put it on Delia, who was now shiverin like mad. But me granny couldn’t save her, an she died.

The next girl te die was Molly, who was eighteen years old. They say she was a real beauty. Gorgeous long wavy hair, down past her waist. She was very religious an probably would have joined the nuns, but she died of consumption. Then me grandfather died, all in nine months. Soon after, me granny got very sick an she was taken inta the Union. Me ma was still only young when she died. The Union used te be called the workhouse. It was a place where sick an destitute people went when there was no hope left.

Me granny left six childre behind te fend fer themselves. Me granny’s maiden sister – she never married – lived close by, an she kept an eye on them. One by one, they took the boat te England, each bringin over the next. Me ma even went at fourteen years old.

There was loads of work for everyone. Because England was tryin te rebuild her cities, after the war with Hitler, who nearly blew them te Kingdom Come. Anyway, for some reason, her brother Larry brought her back te Dublin just before I was born an dumped her with Nelly. So here we are – me, the ma, her sister, Nelly, an Barney.

We all sleep in the one big bed. Me an the ma at one end, an Nelly an Barney at the other. Me aunt Nelly is a real hard chaw – I heard tha word from a neighbour. I suppose it means roarin an laughin one minute, an screamin she’ll kill ye the next. It wouldn’t be a good idea te have a fight with her! One day she sent me fer a Woodbine, an on the way back, I saw tha gobshite Tommy Weaver. I hate him, I do! He thinks he’s so big cos he says he’s five. He doesn’t look it! Anyways, I decided te look like Nelly an put the cigarette in me mouth, I was suckin away like goodo, an yer man was ragin. But by the time I tried te hand it te Nelly, it was all mashed in me mouth, an I was spittin out gobs a tobacca.

Nelly went red as a tomato an then the colour of green grapes. She was gummin fer a cigarette. ‘Gimme me coat!’ she roared, an leapt out the door, screamin at me te come on! She was up in the shop an had managed te browbeat the aul one inta givin her another cigarette by the time I got there. ‘An another thing!’ she was sayin. ‘We were all well reared! If the babby says she didn’t get the cigarette, then she didn’t! We don’t tell lies! An we’re not beggars, we pay our way. So don’t act high an mighty wit me, or I’ll swing for ye! Com on, you!’ she roared at me, an I galloped out behind her, shoutin back at the aul one, ‘Yeah! Tha’s right!’

2

The ma gave me a brush an told me te sweep down the stairs. I was delighted. I was sweepin an hammerin the brush against the aul wooden banister an back te the wall again. The brush was makin an awful noise altogether. Dust was flyin everywhere, an I stopped te watch it swirlin an risin inta the air, caught in the rays of light comin in from the street. Lovely! I went back te me work.

Suddenly the holy priest came up the stairs. He was on his way up te see old Mrs Coleman, who was ailin. I carried on wit me work, an he stopped te stare.

‘You’re a grand girl,’ he said.

‘Yes, Father! I’m helpin me mammy, an I’m nearly kilt tryin te get them clean, so I am.’

The priest had a big red face an a big belly. Me ma says tha’s a sign of the good feedin the priests get. He threw back his head an gave a big laugh, then he patted the top of me head.

I was workin so hard when the priest came back down. He could tell, cos I was bangin an hammerin. An ye couldn’t see a thing, cos I had risen so much dust. An I nearly put his eye out, cos I was wavin the brush so much. I was red in the face meself. The priest admired me so much he put his hand in his pockets an took out a load of coppers an gave them te me. I never saw this much money in me life. I dropped the brush on the stairs an flew down te the shops.

I stood lookin in the shop winda, gazin at the gorgeous cakes, tryin te decide if I’ll have a hornpipe cream first, an then back te me coppers te see if they were real. Me head was spinnin! I had te hold me pocket up wit both hands, cos me pocket was torn an the weight of them was great.

Nelly came up behind me, an I said, ‘Look, Nelly! Lookit wha the priest gave me fer sweepin down the stairs.’

Nelly’s eyes lit up. ‘Ah! Will ye give tha te me te buy the dinner?’

‘No! It’s mine!’

‘I’ll buy you a lovely dinner.’

‘What’ll ye get?’

‘Cabbage an potatoes an a bit of bacon. I promise I’ll cook it fer ye’s all. Just think – a lovely dinner!’

I gave her the money, an she went off in great humour. I ran straight home te tell me ma the great news. She sat there lookin an listenin te me until I got te the bit about Nelly.

‘Ah! Did ye give her the money?’

‘Yeah, Ma, she’s gone te get the dinner.’

‘No, she’s not! She’s gone te the pub. She’ll drink it.’

‘But, Ma, she said she’ll be back wit the dinner.’

‘No! She won’t be back till the money’s gone. Why’d ye give her the money? Why didn’t ye hide it an bring it straight up te me?’

‘She wanted it, Ma, fer the dinner.’

‘Ah, stop annoyin me! You an yer dinner. What am I goin te do fer bread an milk? An lookit! The fire’s gone out. I’ve no coal left te boil the kettle.’

I sat down te listen te the silence of the room. Me ma went back te twitchin her mouth an runnin her fingers through her hair, lookin fer lice. So Nelly was only foolin me!

3

I started school today, cos I’m now four. I’m goin te be a scholar. I’m lookin forward te tha. All the big people said they wished they could go back te school, an these are goin te be the best years of me life!

There’s loads of us sittin at desks, tha’s wha they’re called. We have things called inkwells – tha’s wha ye dip yer pen inta an write on a copybook. But we won’t be doin tha now, cos we’re not real scholars yet.

The teacher shouts down at the young fella sittin beside me, cos he’s eatin his chunk of bread an drippin. We’re not supposed te do tha until we get out te the yard at playtime. She bangs this big long stick on the blackboard. ‘Now, pay attention and sit up straight. No! You can’t go to the toilet, you have to learn to ask in Irish,’ she told a young one who was joggin up an down wit her legs crossed. The pooley streamed down her legs, an the young one was roarin her head off. The teacher had te take her out. We could hear her shoes squelchin, cos they were filled wit piss, an her nose was drippin wit snots. When she got back, the teacher went straight te the blackboard. ‘Now!’ she said. ‘We are going to draw a ...’ an when she was finished, she pointed her stick at a young one an said, ‘What is this?’ pointin at the blackboard.

‘A cup an saucer, Teacher,’ squeaked the young one in a hoarse voice.

‘Yes! Good. And all together now ...’

We all shouted up, ‘A cup an saucer!’

But it was dawnin on me slowly I didn’t like this school business at all. I wouldn’t be able te draw a cup an saucer. School was too hard, an I don’t want te be a scholar. When I got home, I raced up the stairs te tell me ma I was now a

scholar. I’d learnt everythin an didn’t need te go back te school any more. She was sittin by the fire an looked a bit lonely without me. She had a cup of tea an a saucer sittin on top, wit a slice of Swiss roll on it, warmin by the fire fer me dinner. In honour of the occasion.

Me ma says I have te go te school. She holds me hand an keeps tellin me I’ll be grand. The school’s only a few doors down, an I’m back in the school yard before I know wha’s happened. All the childre are millin aroun, waitin fer the door te open. Me ma asks a big young one te mind me, an Tessa who lives across the road takes me hand. Me ma goes off smilin an wavin, an Tessa tells me I’m a big girl now I’m started school, an isn’t it great!

At playtime when they let us out, I try te escape, but the gate is locked. I look te see if the big young one who is supposed te be minding us is watchin, but she’s too busy tryin te placate all the other childre who are cryin fer their mammies. I try te squeeze meself out through the bars, but I can’t get me head out, an I can’t get it back in either! Panic erupts in me. I give a piercin scream, an the other kids come runnin over. They just stand there gapin at me, an some are even laughin. I’ve made a holy show of meself, but I don’t care. A neighbour, Mrs Scally, sees me an rushes over.

‘What ails ye, child?’

‘I want me mammy! Let me out, I want te go home!’

‘Here, don’t struggle. You’ll only make it worse.’

She pushes me, but me head is tightly wedged between the big black bars, an she’s pullin the ears offa me. There’s a big crowd aroun me now, but I can’t see them cos Mrs Scally is suffocatin me wit her shawl. The smell of snuff an porter an sour milk pourin up me nostrils is makin me dizzy.

‘Here, Teacher! I’ll let youse take over. We’re only makin it worse. Maybe we’ll have te get the Fire Brigade. I’ll run an get her mammy.’

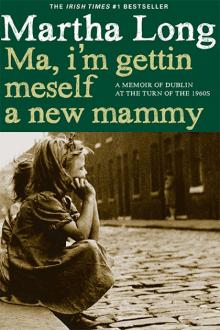

Ma, I'm Gettin Meself a New Mammy

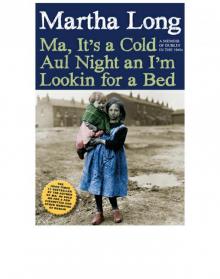

Ma, I'm Gettin Meself a New Mammy Ma, It's a Cold Aul Night an I'm Lookin for a Bed

Ma, It's a Cold Aul Night an I'm Lookin for a Bed Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes

Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes Ma, I've Got Meself Locked Up in the Mad House

Ma, I've Got Meself Locked Up in the Mad House Ma, Jackser's Dyin Alone

Ma, Jackser's Dyin Alone Ma, I've Reached for the Moon an I'm Hittin the Stars

Ma, I've Reached for the Moon an I'm Hittin the Stars Run, Lily, Run

Run, Lily, Run