- Home

- Martha Long

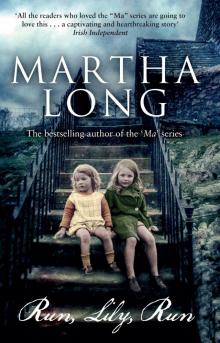

Run, Lily, Run

Run, Lily, Run Read online

About the Book

Lily and Ceily Carney are only seven and twelve when their mother is cruelly taken from them, leaving them at the mercy of the Church and the authorities.

This is a terrifying prospect in 1950s Dublin, where it is likely that the girls will end up in one of Ireland’s notorious Magdalene laundries – a fate they are determined to escape.

When Father Flitters and the ‘Cruelty’ people arrive to take the children into care, Lily and Ceily resist, and a riot breaks out. The girls are helped by kind Mister Mullins and his daughter Delia, but events lead to further tragedy and Lily is left to fend for herself on the dangerous streets. Heartbroken, hungry and vulnerable, she looks like easy prey and it seems there will be no safe haven for her to find.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

About the Author

Also by Martha Long

Copyright

RUN, LILY, RUN

Martha Long

To my ma – thanks, Ma, for bringing me into the world, I know it cost you dearly.

Acknowledgements

I utter a humble thank you to Transworld Publishers, who put trust in me without a manuscript or even the idea for a book of fiction.

Yes, they gave me a contract, they even gave me my beloved Ailsa Bathgate, editor from my old publishers Mainstream – they now gone to sleep and lie among the great and the mighty. Their names Bill Campbell and Peter Mackenzie stand now forever on the roll call of great Scottish publishers.

Yes, but we talk here about Ailsa Bathgate, the editor. She who has suffered me and agonized over every word and every page of my long and sometimes rambling wanderings through the world of words. I am indebted, Transworld, thank you.

Also, the lovely Brenda Kimber, quietly speaking, ‘Keep the head while all around are losing theirs!’

Who but me, and everyone I have touched with my flappings! She is a calm port in a storm! Thank you, Brenda!

Ah, I saved the best for last, Claire Ward, the genius who designs the book jackets and draws you the reader in!

1

‘POOR YOU CEILY! Ye’re only twelve an you have te be all growed up but wasn’t it lucky ye got yer birthday yesterday? Or maybe now ye wouldn’t be a really big girl. An now I’m big too! I got me birthday as well the other day, I’m now seven!’ I hiccupped, smilin now instead a cryin. It was comin wit me havin tha great thought.

‘Lily, if you don’t shrrup I’ll give you a kick up yer skinny arse! I can’t listen to any more of ye – if you’re not cryin ye’re whingin, now you’re ramblin an talkin mad an I’m goin te go outa me mind. SO SHRRUP! SHRRUP, SHRRUP!’ Ceily screamed, tearin at her hair.

I started te cry again, the deep sobs tearin up from me lungs, an huge snots started bubblin down me nose an pourin straight inta me mouth. I stuck me tongue out fer me te lick an taste it, then I swallowed. Now I can still feel the wet heat of it slidin down me neck an disappearin inta me belly as I turned an stared around the darkenin room then looked up te Ceily again, wantin her te make the fear an the pain in me an all me loss go away.

She stared at me wit her eyes red-rimmed an swollen-lookin like she was in shock, but I could see her mind flyin. She was waitin fer the answer te come, then she would take charge. There was no one else.

A few days ago, I came back from school te be told me mammy was in the hospidal. It was only tha night when Ceily arrived in from work, the neighbours, they were waitin te tell her the true, real bad news. They heard the screamin comin from our front room, Mammy had tried te open the street door but collapsed before she could get out. Be the time they got her te hospidal she was dead. Her bowel had burst, poisonin her they said. It ran right through her so fast, there was nothin they or anyone else could do fer her.

I remember when we came back from the hospidal an everyone had finally left, all the friends and neighbours wavin an smilin wantin te get out an home, away from the sorry sad sight of the pair of us – tha’s wha Ceily called it. Then she said it was me standin wit the bony knees rattlin, grippin a tight hold of Molly me dolly, an then herself, Ceily, she bein left te get on wit it in the empty little house now suddenly cold an terribly bare without Mammy. They promised te look in on the pair of us an we were not te be afraid te ask, if we wanted or needed anythin. Then they were gone, rushin out the front door bangin it shut behind them, leavin us wit the emptiness.

We didn’t have a father neither, I often heard me mammy talkin about him. It would be at night when she was sittin around the fire wit Delia Mullins, she was her very best, bestest friend since they were childre goin te school together.

We were supposed te be up in bed sleepin, but not me. I would be out on the landin earwiggin. I would be dyin te know wha they’re talkin about, because childre are not never allowed te hear their business.

So I heard them talkin, whisperin in a low voice, but I still heard anyway, wha they were sayin about me father an tha he was no good. He cleared off, but not before satisfyin a glint in his eye, leavin me mammy te carry me an I less than the size of a green pea. I was the scrapins of the pot, she said, three born dead before me, an in between she lost four childre. She had no relatives, her ma had scarpered off leavin her wit the granny te drag up – tha meanin she havin te rear herself.

I knew all tha from years a listenin, earwiggin Mammy calls … called it.

Now we’re just back from buryin Mammy in her grave. But she’s not really dead. Tha was not my mammy they lowered down tha dark hole then turned an walked away. Sure she’d be freezin wit the cold an left all on her own. I shook me head thinkin about it. No! She’s not dead, an the cheek a people fer sayin tha!

‘Look at the state a them shoes!’ Ceily suddenly screamed.

I stopped roarin, goin inta sudden silence as the pair of us gaped down at the extra inches now plastered te the soles of me one good pair a Sunday shoes. I only wore them fer Mass on Sundays, but got te keep them on if we were then goin out somewhere fancy, like up fer a walk te the Phoenix Park, then down onto O’Connell Street te look in the shop windas. Then the best bit! Into Caffolla’s fer our chips-an-egg tea.

‘Come on, let’s get movin. We better get this fire started te warm the house up, then get you sorted fer school tomorrow, I need te get you a clean frock an socks, an I better polish them shoes,’ she said, lookin down at the caked mud smotherin me lovely brown-leather strapped shoes.

We had stood, sinkin so far down inta the mud I thought we were goin te be buried along wit the coffin as we watched them lower it down, all the way into a deep hole wit our dead mammy inside they said. Terrible it was – it had rained hard non-stop fer three whole days solid, without a let-up.

‘I’m goin te have to cut the toes out a them shoes when you grow out a them. It’s tha or nothin! We don’t have money any more fer luxuries,’ Ceily sniffed, liftin her button nose an throwin back a curly head of coppery bangles, one got in her eye an she whipped it back just as another thought hit her.

‘Wha are we goin te do fer money?’ she suddenly whispered, lettin it out on a breath as the fear hit her, makin her eyes stare out of her head wit the shock. ‘We won’t have Mammy’s money any more! She earned more than twice wha I’m gettin. Not te mention the food tha she brought home.’

I got the picture of Mammy bringin in the cooked food wrapped up in wax paper left over from the mad people’s dinners when she was finished her work. She had a good job – workin wit two others she was cookin an servin the breakfast, the dinners and teas fer all the mad people in the Grangegorman Lunatic Asylum.

‘Does tha mean we’re goin te starve, Ceily?’

‘No don’t be stupid! We’ll manage,’ she snorted, lettin out a roar at me. ‘We’ll have te get you a little job, ye can work after school an over the weekends, I’ll see if there’s anythin part-time goin fer meself at night, an I’ll work the weekends too. Don’t you worry yerself, little Lily! Between the pair of us, we’ll get by!’ she promised, grittin her teeth then fixin her eyes on the now dark room seein her way te the days ahead. Then she muttered, ‘We have te be careful, tell no one nothin. If anyone asks,’ she said slowly, droppin her head an starin right in at my face, holdin me eyes pinned te her.

I listened knowin somethin bad was comin. ‘Say we’re doin grand,’ she warned, narrowin her eyes te put a fear in me. ‘Otherwise the authorities will be down on us like a ton of bricks wantin te whip us away into a convent! We’ll be ended locked up!’ Ceily snorted, takin in a deep breath lettin her face turn sour an her eyes narrow.

‘Why? Wha did we do?’ I said, lettin me mouth drop open an feelin me chest tighten wit a terrible fear – maybe they thought one of us had killed our mammy!

‘Because, you little eegit!’ Ceily roared, losin the rag. ‘You’re too young an I’m not old enough to be mindin you! I’m not even supposed te be mindin meself never mind left school an now workin since last year,’ she snapped, lettin tha thought hit her, makin her even more annoyed an afraid. Then she shook her head whisperin. ‘As sure as night follows day they’ll come after us!’ she muttered, starin inta the distance an talkin te herself wit the eyes gettin tha picture. Then she clamped her mouth shut before openin it again, sayin, ‘Mammy had took a chance an got away wit not sendin me back te school. We needed the money. But now? Oh Jesus, we need to light a penny candle an say a prayer we’ll make it through without gettin caught an comin te harm, Lily!’ she moaned, cryin at me wit her voice keenin an her face pained.

I stared waitin te see if any tears came. But they didn’t, she wouldn’t let them.

2

I CAME RUSHIN back from school wantin te change out of me good school clothes, leave me schoolbag an get goin fast over te old Mister Mullins who owned the corner shop. I didn’t want te lose me new job, this was only me second day an I certainly didn’t want te be late or he might sack me. Ceily had begged an tormented the life outa old Mullins te give me tha job, he didn’t want me, because he thought I wouldn’t be able te carry the heavy bag. An even worser! I wouldn’t be able te manage the big black ‘High Nelly’ bicycle tha went wit the job.

But Ceily wouldn’t take no fer an answer, she knew he was stuck since she heard the whisper Frankie O’Reilly had turned fourteen an left school. He couldn’t do the paper round any more because he was gone off now an got himself a job in the sausage factory – well his da did! An tha was only because he worked there himself. Now Frankie was doin his apprenticeship, startin first wit sweepin an cleanin up all the blood, guts an bones left over from the pigs.

Ceily was over like a bullet, wantin me in quick. ‘Get the job fast before word spreads tha there’s a handy number goin,’ she muttered, lashin herself out the door, headin fer Mister Mullins.

He melted down under the strain of Ceily’s torments. ‘Right,’ he said, but I was only on trial! One false move an I was gone, out the door, no excuses. He had a business te run, an it wasn’t a charity for the Saint Vincent de Paul neither.

* * *

The first thing tha hit me as I rounded the corner onta our street was the little black motor car sittin right outside our front door. I stopped dead in me tracks, peelin the eyes up an down the empty street – nobody has a motor car around here, or even knows anyone who owns one. Yeah, it’s definitely smack-bang sittin right outside our door, so it must be fer us!

Me breath caught, the air started comin up fast through me nose an I clamped me gapin mouth shut. ‘Wha’s happenin? Who’s after us? Oh Mammy!’

I could feel me heart hammerin in me chest as I started te run, I wanted te fly in the other direction but I needed te know. Ceily will be in trouble but there’s a pair of us in it, I can’t leave her by herself.

Me hand was shakin as I tried te get the key in the door, then I heard the voices. I stopped tryin te open the door an put me ear close tryin te hear wha was bein said. I could hear shoutin, tha was Ceily all right, so she is here! She’s not at work. Then there were other voices, all arguin an shoutin over each other.

Somethin very bad is happenin. It’s just over a week now since Mammy died, Ceily said te me last night. She said as well she was expectin trouble, tha I was te keep me eyes open an be ready te act! She didn’t say wha tha meant an I didn’t ask, because she’s worse than Mammy now fer tellin me te stop moiderin her wit me questions.

Before I knew where I was I had turned the key in the lock then found meself standin just inside the sittin room, still holdin onta the doorknob. Me eyes shot te the scullery takin in the crowds a people all millin around packed tight te squashed they were, wit them all thrown together. I could see elbows diggin out wantin a bit of space te make a move. Half the street must be here, along wit the parish priest an even a few strangers.

Me eyes landed on the priest – he was wearin a long black soutane hangin down under a heavy overcoat, an a big wide-rimmed hat shook like mad on his head wit the state he was in.

‘How dare you?!’ he screamed, stampin his shiny laced-up boot an bangin his walkin stick. He was slammin it up an down tha hard, an wit me head followin him I could see he was puttin a dent in our oilcloth wit the rage on him.

‘How DARE you speak to me in that tone of voice and even DARE to answer me back?!’ he roared, throwin the head, makin his face go all purple then gaspin, lettin out huge wheezes tryin te get more breath.

‘YE’RE ONLY THE PARISH PRIEST NOT GOD ALMIGHTY HIMSELF!’ screamed old Granny Kelly from next door, pushin in te face him.

‘ONLY TOO RIGHT! LET ME IN! I’LL TELL HIM!’ shouted Foxy Flynn, throwin back her heavy mass of flamin-red-roarin hair, then diggin her big man’s arms out clearin a way fer herself.

Suddenly he waved the stick, pushin it out through the crowd, makin a lunge fer Ceily. The crowd heaved back, lettin their arse bulge inta the sittin room, then heaved out again as someone grabbed hold a the stick. He slapped hands an got it free, then Ceily screamed as he grabbed a hold of her jumper.

‘NO! Lemme go! Go te hell! You’re not takin me anywhere!’ she roared, twistin his free hand an draggin him wit her inta the sittin room an the crowd heaved wit her, but he wouldn’t let go. She dug her fist in hammerin his hand loose.

‘YOU WILL ALL BE CURSED!’ he shouted, wavin the walkin stick an throwin the head around makin his eyes bulge an his hat wobble givin everyone the evil eye. Then he flew the hand an stick back at Ceily, tryin te grab hold again. She was red in the face darin him, breathin hard an shoutin back inta his face along wit all the neighbours, but the loudest was Nelly Tucks who lived on our other side. She was wearin her grey-an-white-flowered apron wrapped around her, it was still lovely an clean because it was only Tuesday, an she washes it on a Monday. But it looked like she got no time te wrap a scarf around her head an hide the curlers, never mind get them out first thing this mornin. So instead of a lovely mass of curly hair, she was now a holy show wit the pipe cleaners stuck up in the air.

‘Get yourself back outa this house here wit your black-guardin, an don’t be

comin where ye’re not wanted!’ she roared, movin closer te Ceily an takin her, then pullin her tight wrappin her arms around her just in case he might grab hold again.

I stood stuck te the floor gapin wit me mouth open not takin a breath. I could feel me chest an stomach painin me, it had gone tha hard. It was all this holdin meself tight, now I was stiff like a plaster statue, I was holdin meself tha still. An wha’s even worser, I was forgettin te take in air. I shook me head feelin it swimmin an bulged me eyes out tryin te see better, but they won’t work right, I can’t see. An now I can’t make it better. I can’t help meself – it’s all this shock.

I turned me head slowly from one happenin te the next still gapin wit me mouth open, then flyin it when I heard the roars then easin it back again, tryin te take it all in. All the bodies were in the sittin room now pushin an shovin. Father Flitters was tryin te get his hands on Ceily an the rest were tryin te get their hands on him. But there were too many hands in the way an people were gettin themselves clattered, then I heard an agony as someone got hurt.

‘Mind me corns! Youse dirty-lookin eegits, will ye’s not take it easy after breakin me toe?’ screamed Granny Kelly, givin an awful moan then collapsin on top of Biddy Mongrel.

‘Oh Jesus! Get an ambulance! This woman’s on death’s door! Lookit the state a the colour she’s turned! She’s all colours!’ screamed Biddy, givin Granny Kelly a push wit her wantin te get a better look, but instead, pushin her too hard an gettin her sent flyin wit the arms wide open head-first inta the chest of Father Flitters! His arms flapped inta the air savin himself an blindin Nelly Tucks as she got a belt of the flyin stick. The roars were unmerciful an me heart stopped, thinkin now we were all goin te be arrested!

‘MURDER!’ Nelly shouted, lashin back at him wit a dig in the mouth knockin out his false teeth. I watched them flyin through the air then land in the open mouth of Granny Kelly as she toppled wit him, screamin her lungs out. They all ended up in a heap wit Granny Kelly now sittin in his lap. It looked like somethin that ye think should be funny but somehow I couldn’t get a laugh, because it was then me eye caught sight of two people moochin around in our kitchen scullery.

-->

Ma, I'm Gettin Meself a New Mammy

Ma, I'm Gettin Meself a New Mammy Ma, It's a Cold Aul Night an I'm Lookin for a Bed

Ma, It's a Cold Aul Night an I'm Lookin for a Bed Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes

Ma, He Sold Me for a Few Cigarettes Ma, I've Got Meself Locked Up in the Mad House

Ma, I've Got Meself Locked Up in the Mad House Ma, Jackser's Dyin Alone

Ma, Jackser's Dyin Alone Ma, I've Reached for the Moon an I'm Hittin the Stars

Ma, I've Reached for the Moon an I'm Hittin the Stars Run, Lily, Run

Run, Lily, Run